Embedded systems are the unseen intelligence behind countless modern technologies from consumer electronics and automotive systems to medical devices and industrial automation. As the Internet of Things (IoT) and smart technology continue to proliferate, the demand for skilled embedded engineers is at an all-time high.

This guide provides a refined, step-by-step roadmap for aspiring professionals to acquire the necessary skills, build a compelling portfolio, and secure a rewarding position in this dynamic field.

1. Establish a Solid Foundational Knowledge

A successful career in embedded systems is built on a strong understanding of both electronics and computer science.

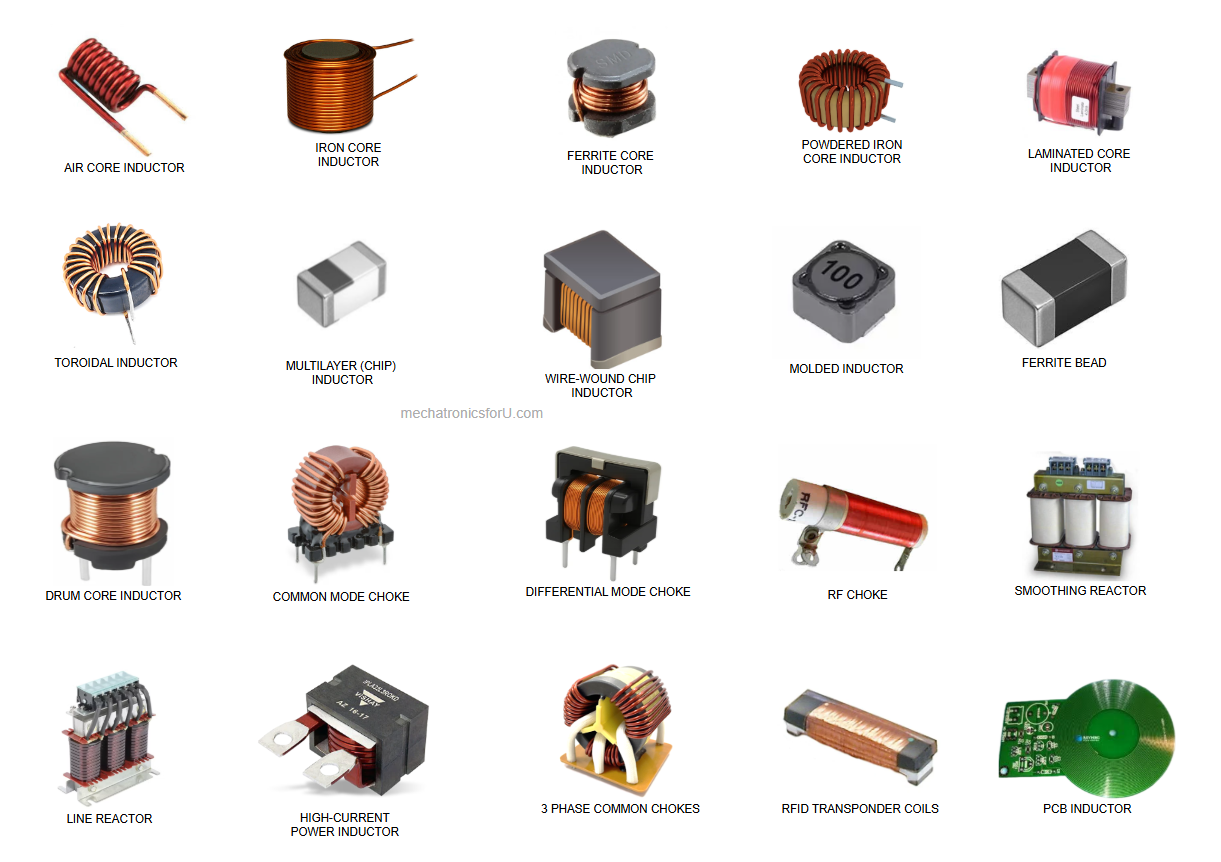

- Electronics Principles: Gain a deep comprehension of core electronics concepts, including Ohm’s Law, Kirchhoff’s laws, and the characteristics of fundamental components like resistors, capacitors, inductors, diodes, and operational amplifiers.

- Digital Electronics: Master the fundamentals of digital logic, including logic gates, combinational and sequential logic circuits, flip-flops, counters, and the architecture of Analog-to-Digital Converters (ADCs) and Digital-to-Analog Converters (DACs).

- Microcontroller Architecture: Study the internal architecture of microcontrollers (MCUs), including their CPU, memory organization (RAM, ROM, Flash), and key peripherals such as Timers, Interrupt Controllers, and GPIOs.

- Practical Application: Begin with accessible development platforms like Arduino for a gentle introduction. Progress to more powerful and industry-standard boards like STM32, ESP32, or PIC to apply your theoretical knowledge to real-world hardware.

2. Master the Art of Embedded Programming

Programming is the primary tool for an embedded systems engineer. Your proficiency in this area will define your capabilities.

- C Programming (The Cornerstone): C is the foundational language for firmware development due to its close-to-hardware access and efficiency. Focus on mastering concepts critical to embedded systems:

- Bitwise Operations: For manipulating hardware registers and flags.

- Pointers and Memory Management: For direct memory access and efficient resource utilization.

- Interrupt Service Routines (ISRs): For handling time-critical events.

volatileKeyword: A crucial concept for preventing compiler optimizations that could break hardware-dependent code.

- C++ (The Next Step): C++ is increasingly used for developing more complex, scalable, and object-oriented embedded applications. Learn its object-oriented features while maintaining an awareness of performance and memory overhead.

- Python: While not for core firmware, Python is invaluable for higher-level tasks such as scripting, automated testing, data analysis, and building back-end services for IoT applications.

3. Gain Substantial Hands-On Experience with Hardware

Theoretical knowledge is insufficient without practical experience. Actively engage with hardware to bridge the gap between code and physical reality.

- Hardware Interfacing: Learn to interface with a variety of components, including sensors (temperature, light, pressure), actuators (motors, servos), displays (LCD, OLED), and relays.

- Communication Protocols: Implement and debug code for essential communication protocols:

- UART: For serial communication with a PC or other devices.

- I²C & SPI: For on-board communication between MCUs and peripherals.

- PWM: For controlling motor speeds and LED brightness.

- CAN & Modbus: For industrial and automotive applications.

- Project-Based Learning: Create projects that integrate multiple skills. Start with simple tasks like a temperature logger and advance to a multi-sensor weather station, a robot with motor control, or an IoT-enabled smart device.

4. Acquire Proficiency with Professional Development Tools

Professional embedded engineers rely on a specific set of tools to streamline their workflow and ensure code quality.

- Integrated Development Environments (IDEs) & Toolchains: Become proficient with professional IDEs like STM32CubeIDE, Keil MDK, or IAR Embedded Workbench. Understand the role of the compiler, assembler, and linker in the build process.

- Debugging Tools: This is a mission-critical skill.

- JTAG/SWD Debuggers: Learn to use these hardware interfaces to set breakpoints, step through code, and inspect memory and registers in real-time.

- Oscilloscopes: Essential for visualizing electrical signals to diagnose timing issues, signal integrity problems, and communication protocol errors.

- Logic Analyzers: Perfect for capturing and analyzing multiple digital signals simultaneously, especially for bus protocols like I²C or SPI.

- Version Control: Master Git and GitHub to manage your code, collaborate effectively, and showcase your projects to potential employers.

- Documentation: Develop the habit of reading and understanding hardware datasheets and reference manuals—these are the bibles for any embedded project.

5. Explore Advanced and Specialized Topics

As you progress, delve into more complex areas to make yourself a more versatile and valuable candidate.

- Real-Time Operating Systems (RTOS): Learn to use an RTOS like FreeRTOS or Zephyr to manage multiple concurrent tasks, handle scheduling, and improve system responsiveness.

- Wireless Communication: Study protocols for connectivity, such as Wi-Fi, Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), LoRaWAN, and cellular technologies.

- Low-Power Design: Understand techniques for optimizing power consumption, which is critical for battery-powered devices and the vast majority of IoT applications.

- Embedded Linux: For more complex applications on single-board computers like the Raspberry Pi or BeagleBone Black, learn about Linux kernel drivers, device trees, and the build systems (e.g., Yocto, Buildroot).

6. Build and Showcase a Strong Project Portfolio

A robust portfolio of hands-on projects is your most effective resume. Employers want to see what you can build, not just what you know.

- Project Ideas:

- Smart Home System: An MCU-controlled system with sensors, actuators, and a mobile app interface.

- BLDC Motor Controller: A complex project demonstrating control theory and PWM expertise.

- Data Logger: A system that collects sensor data and stores it on a non-volatile medium like an SD card.

- Wearable Health Tracker: A project that uses BLE to transmit data from a heart rate or accelerometer sensor.

- Documentation: For each project, write a detailed README file explaining the problem, your solution, the hardware used, and the challenges you faced.

- Online Presence: Upload your projects to GitHub with clean, commented code. Consider creating a personal website or using LinkedIn to showcase your work and share your insights.

7. Demystifying Embedded Systems Troubleshooting

Debugging is an essential and often challenging part of the job. A structured approach to problem-solving will save you countless hours.

Common Problems & Troubleshooting Strategies:

- The Code Doesn’t Run at All:

- Check Power: Use a multimeter to verify the board is receiving the correct voltage.

- Verify Connections: Double-check all wiring and connections. A single misplaced wire can prevent the entire system from booting.

- Look for a Blinking LED: A “Hello World” program that blinks an LED is the first and most critical sanity check. If it works, the MCU is likely running.

- It Runs, But Not as Expected (Logic Errors):

- Use the Debugger: Set breakpoints to halt execution at specific lines. Step through the code line by line and inspect variable values and register states to find where the logic diverges from your expectation.

- Print Statements: Use

printfor serial logging to print variable values and messages at different stages of the code. This is an old but effective way to trace program flow.

- Timing Issues:

- Hardware Timers: If a task needs to execute at a precise interval, use a hardware timer and its interrupts, not software delays (

delay()). - Race Conditions: When multiple tasks or an interrupt and the main loop access the same shared data, use a mutex or disable interrupts temporarily to protect the critical section.

- Hardware Timers: If a task needs to execute at a precise interval, use a hardware timer and its interrupts, not software delays (

- Hardware/Software Integration Problems:

- I²C/SPI Communication Failures: Use a logic analyzer to check the signals. Are the clock and data lines toggling correctly? Are the address and data values correct? Is there a slave acknowledge (ACK) bit?

- Unstable Signals: Use an oscilloscope to check the signal integrity. Look for ringing, overshoot, or glitches that might be causing communication errors. Adjusting pull-up/pull-down resistors or trace routing can sometimes solve these issues.

- Power-Related Issues:

- Brown-Outs: Use an oscilloscope to check the power rail for voltage drops. An unstable power supply can cause the MCU to reset or behave erratically.

- Current Spikes: A motor starting or a wireless module transmitting can draw a large current, causing a voltage drop. Consider using a large capacitor on the power rail to smooth out these spikes.

8. Navigate the Job Market and Land Your First Role

Once your skills and portfolio are ready, you can confidently begin your job search.

- Resume/CV: Tailor your resume to each job description. Highlight your hands-on projects, specific hardware and protocol knowledge (e.g., “Experienced with I²C, SPI, and CAN Bus protocols on STM32 microcontrollers”), and proficiency with professional tools.

- Job Titles to Search: Look for roles like Embedded Software Engineer, Firmware Engineer, IoT Developer, or Robotics Engineer.

- Target Industries: Embedded engineers are in high demand in the automotive, robotics, consumer electronics, aerospace, defense, and medical device sectors.

- Interview Preparation: Be prepared to discuss your projects in detail. Practice explaining your problem-solving process and how you debugged specific issues.

9. Cultivate a Mindset of Continuous Learning

The embedded systems landscape is constantly evolving. Staying at the forefront requires a commitment to lifelong learning.

- Emerging Technologies: Keep an eye on new trends like RISC-V architectures, Edge AI/TinyML, and embedded cybersecurity.

- Community Engagement: Participate in online forums, join local meetups, and follow key industry leaders to stay informed and expand your network.

A career in embedded systems is both intellectually stimulating and deeply rewarding. By focusing on fundamental principles, building practical projects, and embracing a systematic approach to problem-solving, you can build a successful and enduring career in this exciting field.